- Home

- Keir Graff

The Tiny Mansion Page 4

The Tiny Mansion Read online

Page 4

Before I could decide how to answer, Blake pulled something out of his pants pocket and turned so I couldn’t see it. I heard a snick snick sound, then a sizzle, and then he turned back toward me with a big grin on his face.

He was holding a finger-sized firecracker with a burning fuse.

“What are you—”

Before I could say doing, he tossed the firecracker over the log and disappeared into the trees with the dogs on his heels. I froze, feeling caught, and hadn’t taken a step when the firecracker exploded with a POW!

I peeked over the top of the log. The three grown-ups were looking right at my hiding place.

“Who’s there?” called the businessman.

And then they started coming toward me. The lumber-jack was in the lead, taking big strides across the forest floor.

I took off running. I probably should have been thinking about how to get out of the forest and back to the compound, but all I wanted to do was find Blake and make up for the punch I’d thrown and missed.

Bushes whipped my legs as I gave chase, zigzagging between tree trunks, some of them wider than Helen Wheels.

Then I saw a dog’s tail sticking up over a fallen log like a periscope. I jumped over, arms outstretched, ready to hold Blake down and make him pay.

I did the first part, but before I got to the second part, I heard something that made the hair stand up on the back of my neck: the dogs were growling, low, menacing rumbles that started deep in their bellies.

I froze.

Blake grinned, even though I had his shoulders pinned to the dirt.

“You’d better let me up,” he said.

I could hear the grown-ups coming, so I climbed off, and we both wedged ourselves into the opening under the log. The dogs seemed to know what to do and lay down flat, their ears up and alert while Blake patted them soothingly.

Boots crunched nearby. There was a pause and then the wearer of the boots—probably the lumberjack—jumped up on the log, right above our heads.

The dogs looked like they wanted to bolt from their hiding place and start barking, but they were well trained and didn’t make a sound.

The lumberjack stomped back and forth on the log, waiting for the others to catch up. Finally, I heard the other man call to him.

“Do you see anyone?”

“No,” came the answer.

“I think we all know who it is,” said the woman.

In the shadow under the log, I could see Blake grin.

“Let’s not jump to conclusions,” said the businessman.

Slowly, they moved away. We waited a few more minutes before we crawled out from our hiding place. My breathing still wasn’t anywhere close to normal.

“Want to go to my house?” asked Blake.

* * *

■ ■ ■

I’M NOT TOTALLY sure why I agreed to go. After all, Blake was rude, arrogant, and unpredictable. His dogs were scary, his forest was dangerous, and the only other people I’d seen on his land acted like they hated each other. And, if the part about the hidden cameras was true, somebody had a bad case of paranoia.

But Blake also seemed to be the only kid in a thirty-mile radius who was my age. And to be honest, spending a boring day at the compound seemed worse than anything that could happen with him.

I followed him as he moved confidently through the forest, not using a path, while the dogs roamed around us.

“Who were those people?” I asked.

“My dad, and my aunt and uncle.”

“What were they arguing about?”

“They have a business disagreement.”

I ducked under a branch and thought about how Kristen once told me her natural habitat was conference centers and hotel rooms. “Why don’t they meet in an office or something instead of the middle of a forest?”

“They don’t trust each other, so they meet in neutral territory. That place where you saw them is the only part of the forest where all their property lines come together.”

This was getting weirder and weirder.

“And your dad is Reynold Berthold,” I said.

“Yup.”

“Who is he, exactly?”

Blake looked at me the way he’d looked at Helen Wheels, like I was a primitive life-form he’d just discovered. “You actually don’t know? Have you spent your whole life off the grid?”

My face burned, and I could tell I was blushing. Then, to make matters worse, I tripped, and even though I didn’t fall, I had to do this crazy stumble and twirl before I caught my balance.

Blake looked at me and laughed.

“Well, it’s not like you know who my dad is, either,” I said, steadying myself on a tree trunk.

“But he’s not famous, is he?” said Blake.

I thought about turning around right then and there. And maybe I would have, if I’d had any idea how to get back. But the trail was nowhere in sight.

We reached his house just a few minutes later. It was pretty cool, I had to admit.

Then again, cool probably is a little weak. According to Leya’s word-a-day calendar, the house was prodigious (causing amazement or wonder), nonpareil (having no equal), and anomalous (deviating from what is normal, usual, or expected).

Not that I would have told Blake that.

I really do think the architect’s inspiration must have been the crumpled balls of paper containing the unused ideas she threw in the trash—the balls of paper, not the ideas on them. The part of the house I’d seen the day before was the back, and when we went around to the front, there was a garage with a couple futuristic-looking cars inside, and a long driveway that wound off through the trees in the opposite direction of our compound.

Everything in the yard seemed oddly neat and clean, like little robots came out at night to cut the grass and sweep the walks. And when I looked up into the trees, I finally spotted one of the cameras Blake had mentioned. I waved, even though I was tempted to make a much ruder gesture.

“So, what do you think?” asked Blake.

I just shrugged, as if to say, You’ve seen one crumpled-aluminum-foil house, you’ve seen them all.

He seemed disappointed by my reaction. “All the really cool stuff is inside,” he said, opening the front door.

The first thing I noticed was how cold it was. I’ve never been in a morgue, and I hope to keep it that way, but people are always saying something is cold as a morgue, and I guess this is what they mean. My sweat froze, and my arms broke out in goose bumps.

The place was huge, and I’ll be honest, the inside reminded me of a spaceship just as much as the outside. Blake gave me a tour of the ground floor, and in every room he demonstrated some futuristic gadget like it made him bored to do it. In the living room, the windows tinted darker or lighter by voice command; in the kitchen, the fridge made its own shopping list and emailed it to the people who delivered the food; and in the family room, screens rose out of nowhere for TV watching, gaming, or computing.

For some reason, all I could think of was Leya’s old laptop, covered in stickers, marker, and Santi’s gooey fingerprints.

By then I was outright shivering, and I wished I’d brought a sweater—but who wears a sweater in summer?

“We have to keep it cold for all the electronic stuff to work,” said Blake when he finally heard my teeth chattering. “This is a smart mansion, and it’s all based on technology my dad designed. I haven’t even shown you one percent of what it can do. It’s run by a computer that could probably launch a spaceship.”

“Are you sure this isn’t a spaceship?” I asked sarcastically.

It seemed like he actually had to think about it.

“Pretty sure,” he said.

Then he led me back into what he called the office. It didn’t look like a home office; it looked like an office a

t an actual business. There were half a dozen work-stations, each of them with brand-new computers and multiple monitors. In one corner was a glassed-off booth containing a long worktable piled with electronics.

“What is all this for?” I asked.

Blake shrugged. “This is where my dad works on ideas.”

Then he sat down at one of the computers and tapped a few buttons. The large computer screen filled with dozens of tiny rectangles. Each rectangle gave a view inside the house, outside the house, or in the forest. One of them, I noticed, showed the whole cow pasture in front of the NO TRESPASSING sign.

Seeing something move, he clicked on one of the rectangles and expanded it to fill the whole screen. In the forest, the businessman was making his way back to the house.

“Time for you to go,” Blake told me. “My dad’s coming home.”

“Wait,” I demanded. I still had so many questions. “Why are the woods filled with deadly traps?”

Suddenly, a giant man appeared, almost as tall and wide as the doorway he was standing in. It wasn’t Blake’s dad. The top of his bald head was polished to a high shine, and he wore a tracksuit so new it was like he’d just taken it out of the shopping bag. His face reminded me of those sculptures on Easter Island: massive, slablike, and hard as rock.

“There are you,” he said in a gravelly voice. His accent sounded like he came from Russia or one of the countries around there.

“Busted,” groaned Blake.

“I show your friend her home,” said the giant.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Setting a Trap

Blake said goodbye, and the large, rectangular man guided me down a stairway and into the garage, where there was a vehicle that didn’t look futuristic at all: a large, black SUV with tinted windows. He opened the door to the back seat.

“Get on, please,” he said. I guessed he meant get in. His English sounded like a work in progress, but he was close enough that I could tell what he meant: he obviously intended to show me to my home, not show my home to me.

I didn’t budge. “I know how to get home from here,” I told him.

“Forest very dangerous,” he said, motioning toward the SUV like he was trying to sweep me in. His hands were almost as big as broom heads.

“I can take care of myself,” I said, taking a tiny step backward.

He took a big step forward, and it felt like a shadow passing in front of the sun.

“I make sure you get home safe.”

Who was I to argue with a bald giant who looked like he was carved out of stone? I climbed in. Like Trent says, sometimes you have to pick your battles.

He got behind the wheel and started the engine. Naturally, the windows stayed up, and the air-conditioning came on full blast. Didn’t these people ever get cold?

As we went down the driveway, I leaned forward in my seat.

“So what’s your name?” I asked.

“Vladimir,” he said.

“And you work for Mr. Berthold?”

“Yes,” said Vladimir.

“What do you do, exactly?”

“I am manny,” he said with a deep sigh, which was confusing. I guessed he was saying he did many things. Like being a bodyguard, for one.

“Do you want to know my name?” I asked.

“Okay,” he said, not sounding like he really did.

“It’s Dagmar. Do you want to know where I live?”

“I am knowing already.”

That was a little creepy, but considering the cameras in the trees and the computers in their spaceship, the Bertholds could just as easily have had their own satellite, too, that they used to keep an eye on the surrounding landscape. Neither of us said anything else while he drove me back to the compound on winding roads that left the forest and went around it. It was a twenty-minute ride instead of a fifteen-minute walk, which seemed kind of pointless.

When I saw we were almost there, I told Vladimir to pull over and let me out.

“I take you rest of way, is no trouble,” he said.

“Thank you, but I’d rather walk.”

He looked at me in the rearview mirror and seemed to understand what I really wanted, which was not having to explain to Trent and Leya why I’d arrived home in a big, black SUV with tinted windows.

He pulled over and let me out. I almost said, Thanks for the ride, before I remembered I didn’t really want it in the first place. So instead I said, “See you later,” even though I hoped I wouldn’t.

I walked the last few hundred yards up the dirt road while he turned around and drove off. Even though I avoided having Trent and Leya notice how I arrived, they still couldn’t miss the fact that I’d left going one way and returned from the completely opposite direction. Fortunately, they didn’t say anything about it.

The slug funeral was over, and Santi was playing some made-up game involving rocks, sticks, and pine cones that could talk and fly—I didn’t bother asking the rules or the point of the game, because there was a good chance neither existed. Trent was working on his stone wall, which was now about twelve feet long and three feet high and still completely useless. True, it looked nice and the rocks fit together tightly, but the wall still had absolutely no reason to exist.

“You’re just in time, Dagmar,” said Leya. “Lunch is ready!”

For lunch we were having fresh fruit and granola with milk.

Perfect timing.

I waited until everyone else had been served before taking my bowl and heading off to a lawn chair. I hadn’t really thought about the fact that I was sabotaging myself, too.

“I know this is breakfast food,” said Leya, pouring herself soy milk instead of real milk, “but the ice in the cooler is melting, so I figured you guys should use up the milk right away.”

I lifted my spoon to my mouth, thinking I’d just pretend to take a big bite, but I saw Leya looking at me and smiling, so I had to make it real.

Smiling right back at her, I put the mixture in my mouth and rolled it around.

The sliced peach wasn’t bad, but the granola was gritty, and the milk was so vinegary and awful my lips practically puckered back into my head. The moment she turned her head, I spit the whole thing out.

I didn’t have to wait long for their reactions.

Trent frowned and looked thoughtful. “Leya, isn’t this a little . . . crunchier than usual?”

Leya took a small taste. “It’s sandy. Somehow we got something in the granola.”

Santi, who had taken two big bites before he even started chewing, making his cheeks puff out like a squirrel, went, “BLEAH!!!” and spewed sour, gritty granola all over his lap.

“This is awful tasting and gross!” he wailed.

Trent put his spoon down. “I think he’s right. Dagmar, is yours the same?”

I just nodded. I was afraid if I said something, they’d be able to tell from my voice I was lying.

Leya checked our big bin of granola while Trent got the milk out of the cooler and sniffed it. From the look on his face, I could tell he knew the whole jug was ruined.

“Major bummer,” said Trent.

He didn’t seem all that mad about it, which is one of the things that’s frustrating about him: even when he should be mad, you can tell he’s thinking, That’s just the way it is. Honestly, it’s like punching a marshmallow.

But if he was Mr. Easygoing, Leya and Santi more than balanced him out. Even though she had no idea how the granola got ruined, Leya was furious and told everyone they could get their own lunch. Santi, still crying over sour milk, told her he needed a carob bar to get the taste out of his mouth, but she wouldn’t let him have one, which only made him cry more.

I sliced a peach onto a tortilla smeared with sour cream and rolled it up, making a peach burrito. Honestly, it wasn’t half bad.

* * *

THAT AFTERNOON IT was so hot that even reading a book made me want to fall asleep.

Santi was playing with a stick, as usual. The way he waved it around, you’d think he’d found a lightsaber or a magic sword.

I walked down to the creek and wished it had some water in it so I could go swimming, or wading— unfortunately, the best I could do was get my feet muddy.

Bored, I pulled some thin branches off a willow bush and stripped the leaves. The green twigs were soft and pliable (bending freely without breaking), so I wove them into a simple little basket. When a grasshopper landed near me, I sat almost perfectly still, slowly lowering the basket until I could drop it and trap the bug inside. After a frantic effort to get out, it calmed down, and I lifted the basket and cupped the bug in my hands. I got one good look at its alien face before it jumped away and was gone.

Grasshoppers sure are weird-looking.

Then I got another idea.

Without letting anyone see, I borrowed a pocketknife, pruning shears, and a small handsaw from Trent’s toolbox, and an old sheet and some rope from Leya’s art supplies. Then I followed a narrow path along the creek until I had the privacy I needed.

First, I cut some branches that were a lot bigger than the twigs I’d played with—these were as thick as Trent’s thumb. Once I had a dozen, I leaned them together in a beehive shape and tied them at the top with pieces of torn sheet. Then, using lots of smaller, softer branches, none of them bigger around than my little finger, I weaved in and out around the ribs of my upside-down basket. Here and there, I knotted strips of fabric to strengthen it and hold it together.

When I was done, the whole thing came up to my shoulders, which was perfect.

Next, I tied one end of the rope around the top of the basket and the other end around a small, flat rock, which I threw up and over a horizontal branch. Hauling on the rope, I raised the basket until it was about fifteen feet in the air. If you looked right at it, it would be obvious what it was. But if you walked along with your eyes on the ground, you’d never even notice it because it would blend right into the overgrowth.

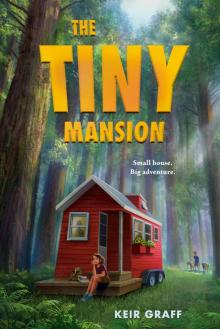

The Tiny Mansion

The Tiny Mansion