- Home

- Keir Graff

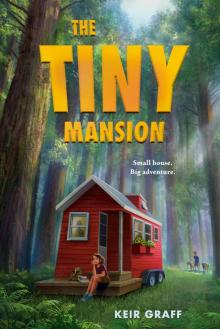

The Tiny Mansion

The Tiny Mansion Read online

Also by Keir Graff

The Matchstick Castle

The Phantom Tower

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

Copyright © 2020 by Keir Graff

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Graff, Keir, 1969– author.

Title: The tiny mansion / Keir Graff.

Description: New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, [2020] | Summary: Twelve-year-old Dagmar and her family spend a summer living off-the-grid in a tiny home parked in the Northern California redwood forest, next door to an eccentric tech billionaire and his very unusual family.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019050344 | ISBN 9781984813855 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781984813862

Subjects: CYAC: Family life—California—Fiction. | Eccentrics and eccentricities—Fiction. | Small houses—Fiction. | Wealth—Fiction. | California—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.G751575 Tin 2020 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019050344

Ebook ISBN 9781984813862

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

pid_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

For Dahlia, Jonah, and Arya

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by Keir Graff

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One: The House in the Forest

Chapter Two: The Tiny Mansion

Chapter Three: A Million Miles from Oakland

Chapter Four: Blake Berthold

Chapter Five: An Argument in the Forest

Chapter Six: The Smart House

Chapter Seven: Setting a Trap

Chapter Eight: Crime and Punishment

Chapter Nine: Around the World in Eighty Foods

Chapter Ten: Mall Runners

Chapter Eleven: Mall Rollers

Chapter Twelve: A Soft Landing

Chapter Thirteen: Blake Loses

Chapter Fourteen: I Win

Chapter Fifteen: The Not Lumberjack

Chapter Sixteen: Charades

Chapter Seventeen: The Human Pretzel

Chapter Eighteen: Licking the Lawn

Chapter Nineteen: Busted

Chapter Twenty: Reynold

Chapter Twenty-One: Smoke

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Stupid Mansion

Chapter Twenty-Three: Rescued?

Chapter Twenty-Four: Not Rescued

Chapter Twenty-Five: The Final Traps

Chapter Twenty-Six: The Last Roundup

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Tree!

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Tiny Fire

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Clean Air at Last

Chapter Thirty: A Complete Write-Off

Chapter Thirty-One: This One Worked

Acknowledgments

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

The House in the Forest

The sign on the fence looked like an invitation.

NO TRESPASSING

KEEP OUT

DANGER

THIS MEANS YOU!!!

I know not everyone would see it that way. Some people would see NO TRESPASSING and stop right there. Even people who can ignore KEEP OUT are probably afraid of DANGER. And there are always people who will be fooled by THIS MEANS YOU into thinking someone specifically wrote the sign for them.

But that’s not the kind of girl I am.

That’s why I had one foot on the tall wire fence, all ready to find out what was so important that the sign writers didn’t want anyone to see it.

The forest of gargantuan redwood trees was dark and wild, and looked like it hadn’t been touched in a million years. I almost expected a left-behind dinosaur to come rumbling through, shouldering aside the massive trunks and flattening plants with its giant feet.

I thought of an adjective from my stepmom Leya’s word-a-day calendar: primeval.

Meaning of or relating to the earliest ages in the history of the world.

The calendar’s three years out of date. My dad, Trent, snagged it out of a dumpster, but Leya didn’t mind. She told him she doesn’t really care what day it is, but she does love learning new words.

I hoisted myself up on the fence and started climbing down the other side, just in time to see the gnome trudging through the field I’d just crossed.

“Dagmar!” whined the gnome. “Wait for me!”

I dropped to the ground, hard enough to make my feet hurt, and rubbed the red lines the wires had made on my palms.

Completely oblivious to the crust of snot on his upper lip, the gnome stopped and stared at the sign. “You’re not s’posed to go in there,” he said, after he finally read it.

The gnome, also known as my five-year-old half brother, Santi, is exactly the kind of person the sign was for.

“Go home, Santi,” I told him.

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll tell them where you are.”

“Don’t tell them where I am. Just tell them you couldn’t find me.”

“But I did find you,” he said, his eyes round as bottle caps.

Welcome to my world.

I turned to go into the trees. “Later, little man.”

“WAIT!” he wailed.

I stopped, thinking, This better be good.

“I don’t know how to get back.”

“Are you serious?” I asked.

I don’t know why I bothered, because I already knew the answer. Santi’s the kind of kid who can’t find his way to the bathroom without GPS.

He nodded.

“Wait here, then,” I told him.

“I’m afraid.”

“Of what?”

He looked around, obviously trying to figure out what to be afraid of.

“Cows?” he said, because the field was fenced and there were a couple of piles of old, dried-up cow poop. At least, I thought it was cow poop.

“We haven’t seen a single cow since we got here!” I told him.

“They’re prob’ly hiding and waiting till I’m alone,” he said, starting to sound like he believed it. “They might stampede.”

I sighed. “If you’re so afraid of cows, then come with me.”

“I’m afraider of that.”

This was getting exasperating. Why didn’t Leya ever look after him? But really, he didn’t have anything to worry about.

“Then go home, Santi,” I said, turning around again, ready to conquer the mysteries of the primeval forest. “You’ll be fine.”

As I stepped into the waist-high ferns and craned my neck up at the towering redwood trees, I heard whimpering, a digging sound, and then a wail of misery. Putting my hands on my hips, I turned around for the third time and saw Santi stu

ck under the fence.

Yes, I laughed, but I was also kind of impressed. I didn’t think the little guy had it in him.

“Come on,” I said, pulling up the bottom of the fence so he could wriggle through. When he stood up, his entire front side was covered in dirt.

“We are gonna get in so much trouble,” he said as he followed me into the trees.

* * *

■ ■ ■

THERE WASN’T A path, so I made sure to take mental pictures of our surroundings as we went along. Exploring is only fun as long as you find your way back. That’s something Trent says, whenever we’re scouting for unobtanium. Unobtanium is what he calls good junk, and sometimes we have to go to strange places to find it: shut-down factories, abandoned industrial sites, and derelict buildings. He calls it recycling, not stealing, because he would never take something someone obviously needed. But a lot of people waste things, so why not put those things to use?

If it’s good stuff, like lumber or Sheetrock or wire or nails, he uses it for his handyman service. If it’s weird stuff, like old motors or broken electronics or rusty pieces of scrap metal, he gives it to Leya for her sculptures.

I’ve been all sorts of places with Trent, from water towers to sewer tunnels, but never to a real forest. Sometimes we take little hikes in the hills behind Oakland, where it’s kind of woodsy, but I never think I’m going to see dinosaurs there because the old mattresses and beer cans ruin the effect.

“I’m hungry,” said Santi, before we’d gone a hundred yards.

“You should have stayed home where there’s food,” I said.

“I also have to pee,” he said.

“There are trees all around us, so take your pick,” I said. “I won’t watch.”

He kept walking, probably trying to think of something else to complain about.

Then we stepped onto a path. It ran left to right, parallel to the fence, so it took me a minute to decide if I wanted to follow it. I was tempted to cross it and go deeper into the forest, but the path seemed more likely to lead us to the reason for NO TRESPASSING.

And maybe there was a good source of unobtanium I could tell Trent about.

We turned left.

We hadn’t gone ten yards when two things happened: I felt a little tug on my ankle at the same moment Santi tripped and fell behind me. I turned around to give him a hand up just as a big patch of the forest floor erupted and flew up toward the sky.

If I hadn’t turned around, I would have been standing right in the middle of it.

Neither Santi nor I had the words for what happened, but he was the first one to say something.

“Dagmar,” he whispered. “This is bad.”

My heart was hammering like a paint mixer. High up in the air, a large net was holding a big clump of dirt and leaves and pine needles and pine cones from the place where I had been walking seconds before. The net, made of thick, knotted rope, creaked and turned gently at the end of a long cable that stretched up into the trees above.

It was obviously a trap meant to catch trespassers.

But we had avoided the DANGER.

I pulled Santi to his feet. I could see now that the tug on my ankle had been a piece of twine, a trip wire that triggered the trap. So if I watched my feet, we shouldn’t stumble into any more traps.

Unless, of course, there were other kinds we didn’t know about.

“Come on,” I told him. “Let’s keep going.”

“I don’t wanna!” he said, his eyes leaking all over his face.

“Don’t you want to learn how to be brave?” I asked.

He shook his head.

“Then you can go back or wait here.”

I kept going down the path, watching carefully for trip wires. I knew he’d start following as soon as I was out of sight. And a little way down the path, I forgot about him completely, because off in the trees, something gleamed like treasure.

I hurried ahead until I could see a huge building made of glass and steel. It looked like a crumpled wad of aluminum foil—no, more like a weird piece of aluminum origami. There wasn’t a straight line on it anywhere, and the light green windows reflected the forest around it so I couldn’t see inside. I couldn’t tell if there even was a front door. Sitting there in the forest, it looked as strange and alien as a spaceship awaiting repairs.

But when some dogs started barking, they didn’t sound extraterrestrial at all: they sounded like the mean old mutts Trent and I sometimes found guarding unobtanium.

I saw the dogs a moment after I heard them. As tall as small horses, they streaked out from behind the building and ran to the edge of the clearing, baying and slobbering as they sniffed the air in my direction. Then they took off straight toward me.

“Let’s go, Santi!” I yelped as I turned and ran.

But Santi wasn’t behind me. Maybe he’d been the smart one, after all.

I raced down the path, wishing I were faster and more graceful. I used to be a great runner, but over the last year I’ve grown so much that sometimes my bones hurt, and now I run like a giraffe on roller skates. That’s what my gym teacher said when she thought I couldn’t hear her.

Coming around a bend, I practically steamrollered the gnome, who was sitting cross-legged in the middle of the path like he was meditating. I lost valuable time stopping and yanking him to his feet again.

“Run, Santi!” I yelled. “Don’t you hear those dogs?”

We plunged off the path toward the fence. Unfortunately, on those short little legs, he was even slower than me.

The dogs were gaining on us, their growls sounding like they came from cavernous, hungry bellies.

Then I heard a noise like a lopsided bowling ball wobbling along an alley. I looked up just in time to see a fat log tumbling down two skids toward us. I had no idea which one of us triggered this trap, but if we didn’t get out of the way, it was going to flatten us like bowling pins.

There was no time to think. I leaped, snagged a shoe on the rough bark of the log as it rolled under me, and fell flat on my stomach.

“Jump, Santi!” I yelled, hoping he had enough spring in those stubby legs to get over it, too.

Raising myself on my forearms, I turned and looked: Santi hadn’t gotten crushed by the log, but he hadn’t exactly cleared it, either. He was running on top of the rolling tree trunk like a lumberjack trying to keep his balance—and if he fell backward, he was going to get pancaked.

“Fall forward!” I yelled, and he did, belly flopping on the ground as the log sped toward the dogs, who turned tail and fled.

Scrambling to my feet, I grabbed Santi and pulled him up. Running was harder on the uneven ground, and we slipped and slid on mossy rocks and rotten wood. Even worse, I think I swallowed a bug.

“This is all your fault!” he panted as we ran. “The sign warned us!”

I didn’t waste my breath answering. Instead, I concentrated on putting one foot in front of the other.

Just as the fence came in view, the barking started again.

As it got louder, I heard a human voice: “After them! Don’t let them get away!”

Well, we were going to get away or die trying.

This section of the fence was half buried in the ground, so the gnome couldn’t go under. Before he could think of a reason to be scared, I grabbed him under the arms and half lifted, half threw him to the top of the fence, where he hung like a big sack of flour. Then I climbed over the top and wedged my feet into the wires so I could help him to the other side.

We dropped to the ground right as the two hounds of heck broke out of the undergrowth, charging straight for us, their teeth snapping like crocodile jaws.

“Come on, Santi!” I pleaded.

We took off in a crouching run and threw ourselves down behind a big bush.

Then we heard the voic

e again.

“Heel!” it said.

Peeking out, I saw the two dogs trot away and sit next to a boy with dark hair and a scowling face. He was shorter than me but was probably about my age, and he might have been cute if I liked boys, which I don’t. My friends at school probably would have said he looked like some movie star I’d never heard of, but all I noticed was his frown and the fact that his hair was perfectly combed.

He walked up to the fence and peered through, looking for us. I ducked down and put my finger to my lips so Santi wouldn’t break the silence and give away our location by saying something brilliant like “I peed my pants!”

We crouched behind the bush for a long time, so long that I started to worry the boy had climbed the fence or opened a gate for his monster dogs. We didn’t hear them coming, but we didn’t hear them leave, either. Finally, I got up my courage and looked.

They were gone.

CHAPTER TWO

The Tiny Mansion

Two weeks earlier, I’d come home to find a tiny red house parked at the curb outside our apartment building in Oakland. It was the second-to-last day of school, and everything was copacetic (copacetic: in excellent order)—or at least as normal as things ever got in my mixed-up family. True, we had been eating Crock-Pot beans for a whole week, and Santi’s rocket-powered butt was making the bedroom we shared smell so bad my eyes still water just thinking about it. Also true, Leya said if I wanted new summer clothes, I’d have to pick them out at the Salvation Army. And, yes, it was our third apartment in the last eighteen months. But summer was almost here, and I was looking forward to hanging out with my friends when I wasn’t hunting unobtanium with Trent.

But there was the house. I recognized it right away, of course, because Trent had been building it for a while. It wasn’t like one of his usual projects, where he would fix somebody’s porch or plumbing with unobtanium parts and then get paid in backyard eggs and veggies or some other kind of barter. This one was for two customers who had good jobs and wanted a little weekend house but hadn’t decided where to put it yet. They wanted it to be really nice, so Trent built it with fresh lumber and all-new hardware, even windows that came already made in a box. Every now and then I’d go to the warehouse where he kept it and watch him work, sometimes helping if he let me.

The Tiny Mansion

The Tiny Mansion